(For a pdf version click

here.)

Gene Fama’s Nobel Prize Efficient Markets Gene’s first really famous contributions came in the late 1960s and early 1970s under the general theme of “efficient markets.” “Efficient Capital Markets: a Review of Theory and Empirical Work’’ [15] is often cited as the central paper. (Numbers refer to

Gene’s CV.)

“Efficiency” is not a pleasant adjective or a buzzword. Gene gave it a precise, testable meaning. Gene realized that financial markets are, at heart, markets for information. Markets are “informationally efficient” if market prices today summarize all available information about future values. Informational efficiency is a natural consequence of competition, relatively free entry, and low costs of information in financial markets. If there is a signal, not now incorporated in market prices, that future values will be high, competitive traders will buy on that signal. In doing so, they bid the price up, until the price fully reflects the available information.

Like all good theories, this idea sounds simple in such an overly simplified form. The greatness of Fama’s contribution does not lie in a complex “theory” (though the theory is, in fact, quite subtle and in itself a remarkable achievement.) Rather “efficient markets” became the organizing principle for 30 years of empirical work in financial economics. That empirical work taught us much about the world, and in turn affected the world deeply.

For example, a natural implication of market efficiency is that simple trading rules should not work, e.g. “buy when the market went up yesterday.” This is a testable proposition, and an army of financial economists (including Gene, [4], [5],[ 6]) checked it. The interesting empirical result is that trading rules, technical systems, market newsletters and so on have essentially no power beyond that of luck to forecast stock prices. It’s not a theorem, an axiom, or a philosophy, it’s an empirical prediction that could easily have come out the other way, and sometimes did.

Similarly, if markets are informationally efficient, the “fundamental analysis” performed by investment firms has no power to pick stocks, and professional active managers should do no better than monkeys with darts at picking stocks portfolios. This is a remarkable proposition. In any other field of human endeavor, we expect seasoned professionals systematically to outperform amateurs. But other fields are not so ruthlessly competitive as financial markets! Many studies checked this proposition. It’s not easy. Among other problems, you only hear from the winners. The general conclusion is that markets are much closer to efficient here than anybody thought. Professional managers seem not to systematically outperform well-diversified passive investments. Again, it is a theory with genuine content. It could easily have come out the other way. In fact, a profession that earns its salary teaching MBA students could ask for no better result than to find that better knowledge and training lead to better investment management. Too bad the facts say otherwise.

If markets are informationally efficient, then corporate news such as an earnings announcement should be immediately reflected in stock prices, rather than set in motion some dynamics as knowledge diffuses. The immense “event study” literature, following [12] evaluates this question, again largely in the affirmative. Much of the academic accounting literature is devoted to measuring the effect of corporate events by the associated stock price movements, using this methodology.

Perhaps the best way to illustrate the empirical content of the efficient markets hypothesis is to point out where it is false. Event studies of the release of inside information usually find large stock market reactions. Evidently, that information is not incorporated ex-ante into prices. Restrictions on insider trading are effective. When markets are not efficient, the tests verify the fact.

These are only a few examples. The financial world is full of novel claims, especially that there are easy ways to make money. Investigating each “anomaly” takes time, patience and sophisticated statistical skill; in particular to check whether the gains were not luck, and whether the complex systems do not generate good returns by implicitly taking on more risk. Most claims turn out not to violate efficiency after such study.

But whether “anomalies” are truly there or not is beside the point for now. For nearly 40 years, Gene Fama’s efficient market framework has provided the organizing principle for empirical financial economics. Random walk tests continue. For example, in the last few years, researchers have been investigating whether “neural nets” or artificial intelligence programs can forecast short run stock returns, and a large body of research is dissecting the “momentum effect,” a clever way of exploiting very small autocorrelations in stock returns to generate economically significant profits. Tests of active managers continue. For example, a new round of studies is examining the abilities of fund managers, focusing on new ways of sorting the lucky from the skillful in past data. Hedge funds are under particular scrutiny as they can generate apparently good returns by hiding large risks in rare events. Event studies are as alive. For example, a large literature is currently using event study methodology to debate whether the initial public offerings of the 1990s were “underpriced” initially, leading to first-day profits for insiders, and “overpriced” at the end of the first day, leading to inefficiently poor performance for the next six months. It’s hard to think of any other conceptual framework in economics that has proved so enduring.

Development and testing of asset pricing models and empirical methods Financial economics is at heart about risk. You can get a higher return, in equilibrium, in an efficient market, but only if you shoulder more risk. But how do we measure risk? Once an investment strategy does seem to yield higher returns, how do we check whether these are simply compensation for greater risk?

Gene contributed centrally to the developments of the theoretical asset pricing models such as the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) that measure the crucial components of risk ([9], [11], [13], [14], [16], [17], [20], [21], [26], [31], [75], 79]). [14] is a classic in particular, for showing how the CAPM could apply beyond the toy two period model.

However, Gene’s greatest contribution is again empirical. “Risk, Return and Equilibrium: Empirical Tests” with James MacBeth [25] stands out. The Capital Asset Pricing model specifies that assets can earn higher returns if they have greater “beta” or covariance with the market portfolio. This paper convincingly verified this central prediction of the CAPM.

Its most important contribution, though, lies in methods. Checking the prediction of the CAPM is difficult. This paper [25] provided the “standard solution” for all of the statistical difficulties that survives to this day. For example, we now evaluate asset pricing theories on portfolios, sorted on the basis of some characteristic, rather than using individual stocks; we often use 5 year rolling regressions to estimate betas. Most of all, The Journal of Finance in 2008 is still full of “Fama MacBeth regressions,” which elegantly surmount the statistical problem that returns are likely to be correlated across test assets, so N assets are not N independent observations. Gene's influence is so strong that even many of the arbitrary and slightly outdated parts of this procedures are faithfully followed today. What they lose in econometric purity, they gain by having become a well-tested and trusted standard.

"The adjustment of stock prices to new information" [12] is another example of Gene's immense contribution to methods. As I mentioned above, this paper, with over 400 citations, launched the entire event study literature. Again, actually checking stock price reactions to corporate events is not as straightforward as it sounds. Gene and his coauthors provided the "standard solution" to all of the empirical difficulties that survives to this day. Similarly, his papers on interest rates and inflation led the way on how to impose rational expectations ideas in empirical practice.

Simply organizing the data has been an important contribution. Gene was central to the foundation of the Center for Research in Securities Prices, which provides the standard data on which all U.S. stock and bond research are done. The bond portfolios he developed with Robert Bliss are widely used. He instigated the development of a survivor bias free mutual fund database, and the new CRSP-Compustat link is becoming the standard for a new generation of corporate finance research, again led by Gene's latest efforts ([80] [83] [85], [87]).

This empirical aspect of Gene's contribution is unique. Gene did not invent fancy statistical "econometric techniques," and he is not a collector of easily observed facts. Gene developed empirical methods that surmounted difficult problems, and led a generation through the difficult practical details of empirical work. The best analogy is the controlled clinical trial in medicine. One would call that an empirical method, not a statistical theorem. Gene set out the empirical methods for finance, methods as central as the clinical trial is to medicine, empirical methods that last unquestioned to this day.

Predictable returns Many economists would have rested on their laurels at this point, and simply waited for the inevitable call from the Nobel Prize committee. The above contributions are widely acknowledged as more than deserving in the financial and macroeconomics community. But Gene’s best and most important work (in my opinion) still lies ahead.

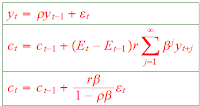

The efficient markets work of the 1960s and 1970s found that stock returns are not predictable ("random walks") at short horizons. But returns might well still be predictable at long horizons, if investors’ fear of risk varies over time. For example, in the depths of a recession few people may want to hold risky assets, as they are rightly worried about their jobs or the larger economic risks at these times. This quite rational fear lowers the demand for risky assets, pushing down their prices and pushing up subsequent returns. If this is true, we could predict good and bad returns in the stock market based on the state of the economy, even though the market is perfectly efficient (all information is reflected in current prices). This argument is obviously much more plausible at business cycle frequencies than at short horizons, which is why the early tests concentrated on short horizons. Gene’s next great contribution, in the 1980s, was to show how returns are predictable at long horizons.

Though the last paragraph makes it sound like an easy extension, I cannot begin to describe what a difficult intellectual leap this was for Gene as well as for the rest of the financial economics profession. Part of the difficulty lay in the hard won early success of simple efficient markets in its first 10 years. Time after time, someone would claim a system that could “beat the market” (predict returns) in one way or another, only to see the anomaly beat back by careful analysis. So the fact that returns really are predictable by certain variables at long horizons was very difficult to digest.

The early inklings of this set of facts came from Gene’s work on inflation ([30], [32], [35], [37], [39], [43], [44], [49]). Since stocks represent a real asset, they should be a good hedge for inflation. But stock returns in the high inflation of the 1970s were disappointing. Gene puzzled through this conundrum to realize that the times of high inflation were boom times of low risk premiums. But this means that risk premiums, and hence expected returns, must vary through time.

Gene followed this investigation in the 1980s with papers that cleanly showed how returns are predictable in stock ([55], [58], [59], [62]), bond ([50], [52], [57], [62], [64]), commodity ([56], [60]) and foreign exchange ([40], [51]) markets, many with his increasingly frequent coauthor Ken French. These papers are classics. They define the central facts that theorists of each market are working on to this day. None have been superseded by subsequent work, and these phenomena remain a focus of active research.

(I do not mean to slight the contributions of others, as I do not mean to slight the contribution of others to the first generation of efficient markets studies. Many other authors examined patterns of long horizon return predictability. This is a summary of Gene’s work, not a literature review, so I do not have space to mention them. But as with efficient markets, Gene was the integrator, the leader, the one who most clearly saw the overarching pattern in often complex and confusing empirical work, and the one who established and synthesized the facts beyond a doubt. Many others are often cited for the first finding that one or another variable can forecast returns, but Gene’s studies are invariably cited as the definitive synthesis.)

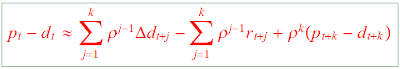

The central idea is that the level of prices can reveal time varying expected returns. If expected returns and risk premiums are high, this will drive prices down. But then the “low” price today is a good signal to the observer that returns will be high in the future. In this way stock prices relative to dividends or earnings predict stock returns; long term bond prices relative to short-term bond prices predict bond returns; forward rates relative to spot rates predict bond and foreign exchange returns, and so forth. Low prices do not cause high returns any more than the weatherman causes it to snow.

This work shines for its insistence on an economic interpretation. Other authors have taken these facts as evidence for “fads” and “fashion” in financial markets. This is a plausible interpretation, but it is not a testable scientific hypothesis; a “Fad” is a name for something you don’t understand. Gene’s view, as I have articulated here, is that predictable returns reflect time-varying risk premia related to changing economic conditions. This is a testable view, and Gene takes great pain to document empirically that the high returns come at times of great macroeconomic stress, (see especially [60], [62]). This does not prove that return forecastability is not due to “fads,” anymore than science can prove that lightning is really not caused by the anger of the Gods. But had it come out the other way; had times of predictably high returns not been closely associated with macroeconomic difficulties, Gene’s view would have been proven wrong. Again, this is scientific work in the best sense of the word.

The influence of these results is really only beginning to be felt. The work of my generation of theoretically inclined financial economists has centered on building explicit economic models of time-varying macroeconomic risk to explain Fama and French’s still unchallenged findings. Most of corporate finance still operates under the assumption that risk premia are constant over time. Classic issues such as the optimal debt/equity ratio or incentive compensation change dramatically if risk premia, rather than changing expectations of future profits, drive much price variation. Most of the theory of investment still pretends that interest rates, rather than risk premia, are the volatile component of the cost of capital. Portfolio theory is only beginning to adapt. If expected returns rise in a recession, should you invest more to take advantage of the high returns? How much? Or are you subject to the same additional risk that is, rationally, keeping everyone else from doing so? Macroeconomics and growth theory, in the habit of considering models without risk, or first order approximations to such models in which risk premia are constant and small, are only beginning to digest the fact that risk premia are much larger than interest rates, let alone that these risk premia vary dramatically over time.

In these and many other ways, the fact that the vast majority of stock market fluctuation comes from changing expected returns rather than changing expectations of future profits, dividends, or earnings, will fundamentally change the way we do everything in financial economics.

The cross section, again We are not done. A contribution as great as any of these, and perhaps greater still, lies ahead.

If low prices relative to some multiple (dividends, earnings, book value) signal times of high stock returns, perhaps low prices relative to some multiple signal stocks with high risks and hence high returns. In the early 1990s, Gene, with Ken French, started to explore this idea.

The claim was old, that “value stocks” purchased for low prices would yield higher returns over the long run than other stocks. This claim, if true, was not necessarily revolutionary. The Capital Asset Pricing Model allows some asset classes to have higher average returns if they have higher risk, measured by comovement with the market return, or “beta.” So, if the value effect is not a statistical anomaly, it could easily be consistent with existing theory, as so many similar effects had been explained in the past. And it would be perfectly sensible to suppose that “value” stocks, out of favor, in depressed industries, with declining sales, would be extra sensitive to declines in the market as a whole, i.e. have higher betas. The “value premium” should be an interesting, but not unusual, anomaly to chase down in the standard efficient markets framework.

Given these facts, Gene and Ken’s finding in “The Cross Section of Expected Stock Returns” [68] was a bombshell. The higher returns to “value stocks” were there all right, but CAPM betas did nothing to account for them! In fact, they went the wrong way -- value stocks have lower market betas. This was an event in Financial Economics comparable to the Michelson-Morley experiment in Physics, showing that the speed of light is the same for all observers. And the same Gene who established the cross-sectional validity of the Capital Asset Pricing Model for many asset classifications in the 1970s was the one to destroy that model convincingly in the early 1990s when confronted with the value effect.

But all is not chaos. As asset pricing theory had long recognized the possibility of time varying risk premia and predictable returns, asset pricing theory had recognized since the early 1970s the possibility of “multiple factors” to explain the cross section. Both possibilities are clearly reflected in Gene's 1970 essay. It remained to find them. Though several “multiple factor” models had been tried, none had really caught on. In a series of papers with Ken French, ([72], [73], [78], and especially [74]) Gene established the “three factor model” that does successfully account for the “value effect.”

The key observation is that “value stocks” -- those with low prices relative to book value -- tend to move together. Thus, buying a portfolio of such stocks does not give one a riskless profit. It merely moves the times at which one bears risk from a time when the market as a whole declines, to a time when value stocks as a group decline. The core idea remains, one only gains expected return by bearing some sort of risk. The nuance is that other kids of risk beyond the market return keep investors away from otherwise attractive investments.

Since it is new, the three-factor model is still the object of intense scrutiny. What are the macroeconomic foundations of the three factors? Are there additional factors? Do the three factors stand in for a CAPM with time-varying coefficients? Once again, Gene’s work is defining the problem for a generation.

Though literally hundreds of multiple-factor models have been published, the Fama-French three-factor model quickly has become the standard basis for comparison of new models, for risk-adjustment in practice, and it is the summary of the facts that the current generation of theorists aims at. It has replaced the CAPM as the baseline model. Any researcher chasing down an anomaly today first checks whether anomalously high returns are real, and then checks whether they are consistent the CAPM and the Fama-French three factor model. No other asset pricing model enjoys this status.

Additional contributions Gene has made fundamental contributions in many other areas. His early work on the statistical character of stock returns, especially the surprisingly large chance of large movements, remains a central part of our understanding.([1], [2], [3], [4]). He has made central contributions to corporate finance, both its theory ([24], [36], [38], [42], [46], [47], [54], [63], [75]) and empirical findings ([10], [29], [80], [83], [85], [86], [87]). Some of the latter begin the important work of integrating predictable returns and new risk factors into corporate finance, which will have a major impact on that field. These are as central as his contributions to asset pricing that I have surveyed here; I omit them only because I am not an expert in the field. He has central contributions to macroeconomics and the theory of money and banking ([40], [41], [48], [49], [53], [70]).

The case for a Prize I have attempted to survey the main contributions that must be mentioned in a Nobel Prize; any of these alone would be sufficient. Together they are overwhelming. Of course, Gene leads most objective indicators of influence. For example, he is routinely at or near the top of citations studies in economics, as well as financial economics.

The character of Gene’s work is especially deserving of recognition by a Nobel Prize, for a variety of reasons.

Empirical Character. Many economists are nominated for Nobel prizes for influential theories, ideas other economic theorists have played with, or theories seem to have potential in the future for understanding actual phenomena. Gene’s greatness is empirical. He is the economist who has taught us more about how the actual financial world works than any other. His ideas and organizing framework guided a generation of empirical researchers. He established the stylized facts that 30 years of theorists puzzle over. Gene’s work is scientific in the best sense of the word. You don’t ask of Gene, “what’s your theory?” you ask “what’s your fact?” Finance today represents an interplay of fact and theory unparalleled in the social sciences, and this fact is largely due to Gene’s influence.

Ideas are Alive. Gene’s ideas are alive, and his contributions define our central understanding of financial markets today. His characterizations of time varying bond, stock, and commodity returns, and the three-factor model capturing value and size effects remain the baseline for work today. His characterization of predictable foreign exchange returns from the early 1980s is still one of the 2 or 3 puzzles that define international finance research. The critics still spend their time attacking Gene Fama. For example, researchers in the “behavioral finance” tradition are using evidence from psychology to give some testable content to an alternative to Gene’s efficient market ideas, to rebut caustic comments like mine above about “fads.” This is remarkable vitality. Few other idea from the early 1970s, including ideas that won well-deserved Nobel prizes, remains an area of active research (including criticism) today.

Of course, some will say that the latest crash "proves" markets aren't "efficient." This attitude only expresses ignorance. Once you understand the definition of efficiency and the nature of its tests, as made clear by Gene 40 years ago, you see that the latest crash no more "proves" lack of efficiency than did the crash of 1987, the great slide of 1974, the crash of 1929, the panic of 1907, or the Dutch Tulip crisis. Gene's work, and that of all of us in academic finance, is about serious quantiative scientific testing of explicit economic models, not armchair debates over anecdotes. The heart of efficient markets is the statement that you cannot earn outsize returns without taking on “systematic” risk. Given the large average returns of the stock market, it would be inefficient if it did not crash occasionally.

Practical importance. Gene’s work has had profound influence on the financial markets in which we all participate.

For example, In the 1960s, passively managed mutual funds and index funds were unknown. It was taken for granted that active management (constant buying and selling, identifying "good stocks" and dumping "bad stocks") was vital for any sensible investor. Now all of us can invest in passive, low cost index funds, gaining the benefits of wide diversification only available in the past to the super rich (and the few super-wise among those). In turn, these vehicles have spurred the large increase in stock market participation of the last 20 years, opening up huge funds for investment and growth. Even proposals to open social security systems to stock market investment depend crucially on the development of passive investing. The recognition that markets are largely “efficient,” in Gene’s precise sense, was crucial to this transformation.

Unhappy investors who lost a lot of money to hedge funds, dot-coms, bank stocks, or mortgage-backed securities can console themselves that they should have listened to Gene Fama, who all along championed the empirical evidence – not the “theory” – that markets are remarkably efficient, so they might as well have held a diversified index.

Gene's concepts, such as "efficiency" or that value and growth define the interesting cross section of stock returns are not universally accepted in practice, of course. But they are widely acknowledged as the benchmark. Where an active manager 40 years ago could just say "of course," now he or she needs to confront the overwhelming empirical evidence that most active managers do not do well. Less than 10 years after Fama and French's small/large and value/growth work was first published, mutual fund companies routinely categorize their products on this dimension. (See www.vanguard.com for example.)

Influence in the field. Finally, Gene has had a personal influence in the field that reaches beyond his published work. Most of the founding generation of finance researchers got their Ph. D’s under Gene Fama, and his leadership has contributed centrally to making the Booth School at the University of Chicago such a superb institution for developing ideas about financial economics.